The Albanian Pavilion at the International Architecture Biennale, 19th Edition, Venice 2025.

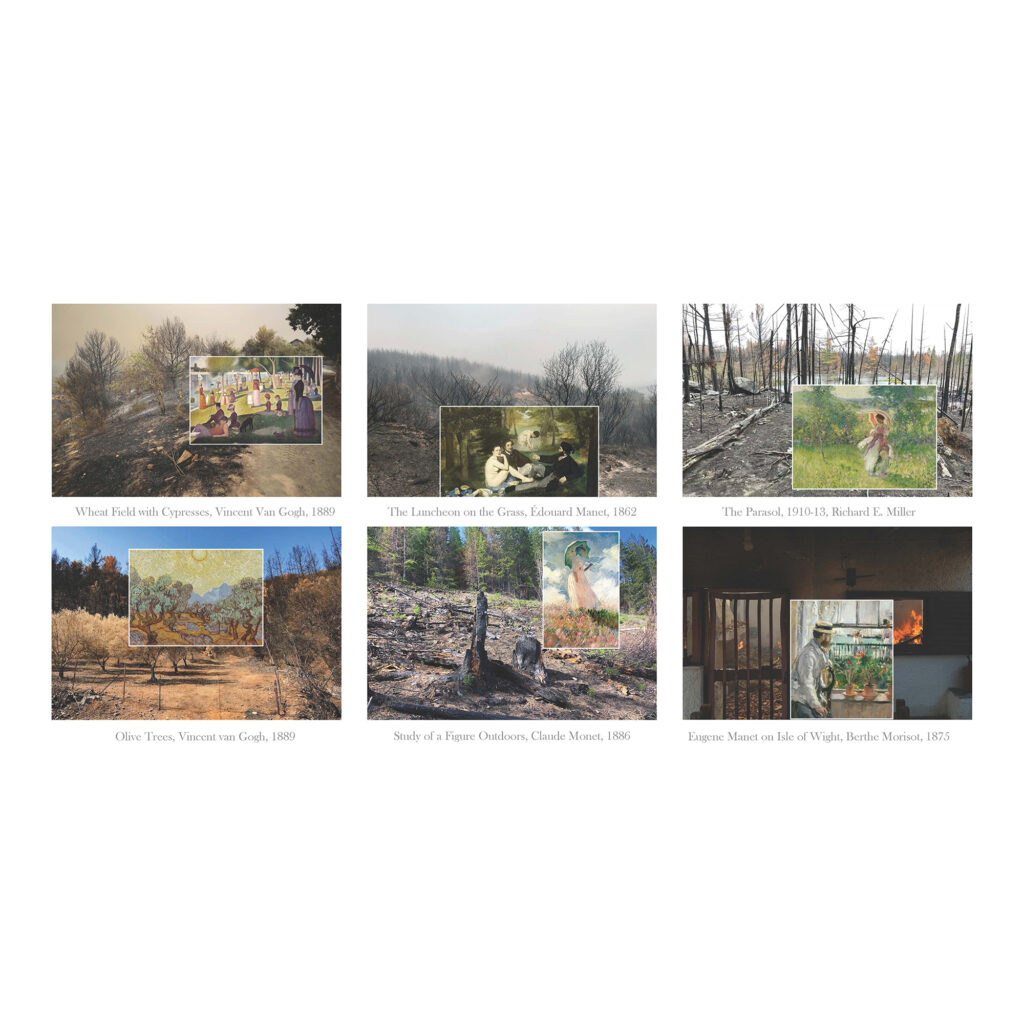

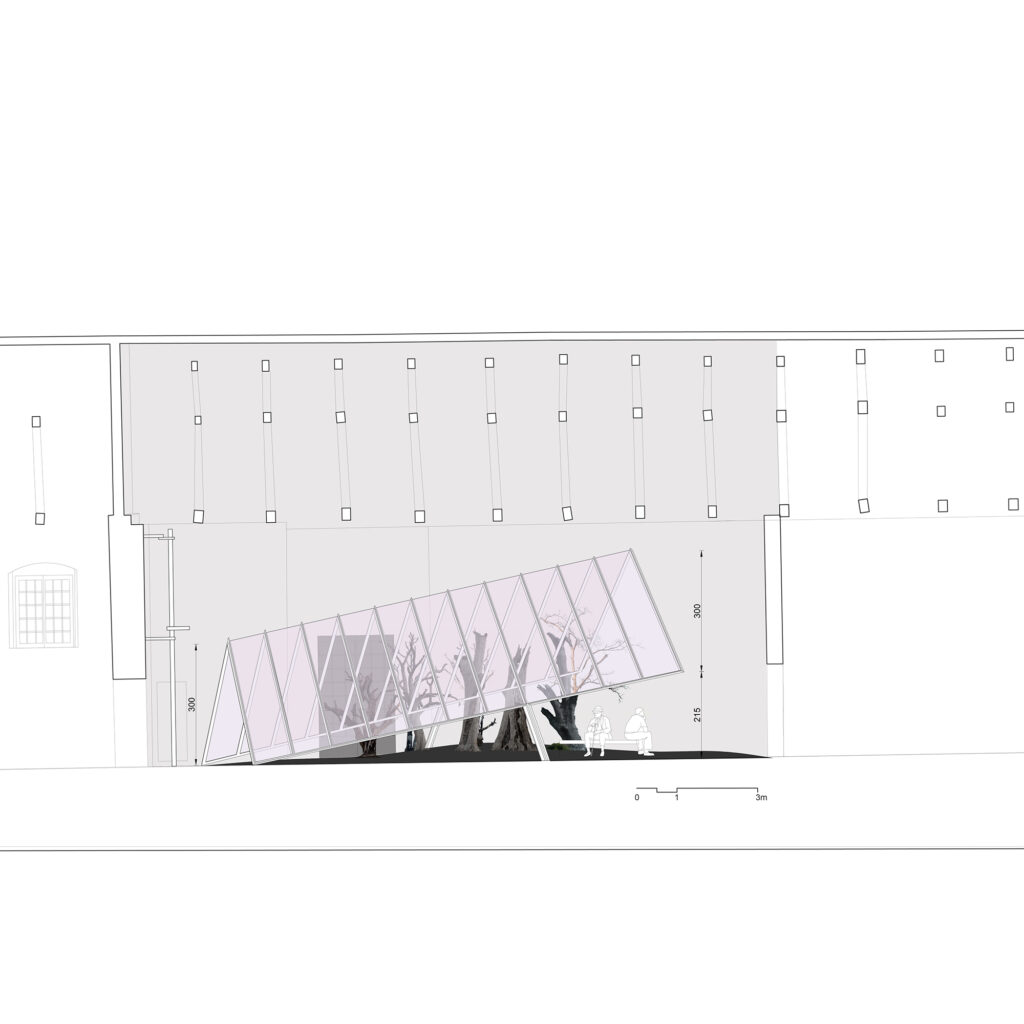

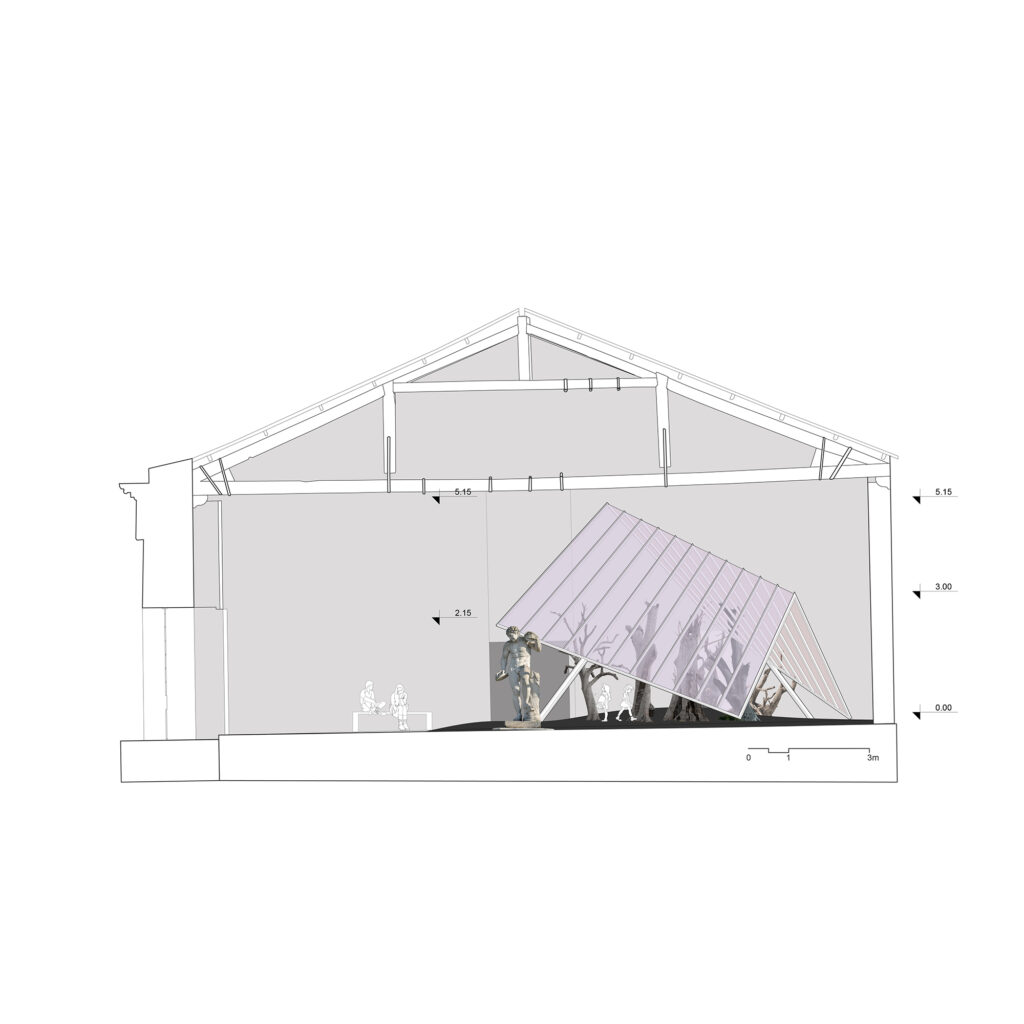

Claude Monet maintained a continuous dialogue with nature and its places through a thematic and chronological arrangement; Vincent van Gogh went in search of color and light in the South of France. As impressionism and post-impressionism focused on capturing the beauty of nature, an abandonment of any human presence in the landscapes was obvious, a testimony to their commitment to isolate themselves in nature. So influential has nature been throughout the centuries that several ways of replicating it have been invented. The story goes that the first ever greenhouse was created in Rome in 30 A.D. when Emperor Tiberius became sick and was prescribed to eat one cucumber a day. Allegorically, the greenhouse of the Victorian era is brought to this pavilion as a contemporary shelter for the unfortunate plants of the Mediterranean region which did make it to the Venice Biennale, but, unfortunately burnt.

Humans have been altering nature for thousands of years, but now some forests aren’t growing back after wildfires. It is the time for us to recognize the ability of the natural environment to self heal and adjust its biodiversity behaviors. It is the time that we respond to this as intelligens, natural and artificial both, and collectively. As this exhibition will cast architects in the role of “mutagens” stimulating natural evolutionary processes and sending them off in new directions, this Pavilion hopes to radically alter the perception of the “inevitable” and incentivize new ways of approaching it.

| LOCATION | The Venetian Arsenal, Venice, Italy |

| YEAR | 2024 |

| CLIENT | Ministry of Economy, Culture and Innovation – Albania |

| STATUS | Competition |

| PROGRAM | Pavilion |

| PROJECT ARCHITECT | Julian Beqiri |

The Victorian greenhouse, as an iconic feature in the gardens of affluent homeowners, provided protection of tender or out-of-season plants against excessive cold or heat. But, how much would humanity have cared for a Victorian greenhouse located in the Burnt Forests?! Would they make a good path and walk it every day? Would they monitor the temperature and strictly avoid overheating? Would they water it lightly

to avoid causing the seeds to float up to the surface? Would they work on creating healthy convection currents of air? Would they resort to shading when other methods of cooling do not work? They would certainly do. So, what makes a forest such a disadvantageous entity exempt of care and commitment?!

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Faunus was the rustic god of the forest, plains and fields. He eventually became primarily a woodland deity, the sounds of the forest being regarded as his voice. Analogically, a replica of his statue located in Schloss Nordkirchen, Germany, is brought to this Biennale as the main “load-bearing column” supporting the pavilion. The structure itself is designed to be of aluminum structural glazing standing on top of a hilly artificial terrain covered in black soil and ashes.

Considering nature and society as two separate entities would be the first step on the way to reevaluating our positioning towards nature; towards our growing hegemony of control over its resources, and further, our competence to intervene through the process of building. This should certainly not be seen as semiotic and semantic veils which only temporarily hide humanity’s relentless engagement of alienating the environment.

GONE WITH THE WIND acknowledges human dominance over the natural landscape but showcases its consequence as an act of sheer will undressed from political correctness or other forms of marginalized opinion. While all that is solid probably truly melts into air (“All that is solid melts into air, and communities and lives being destroyed by the economic exploitation inherent to a capitalist society” – Karl Marx, London, 1856), this pavilion calls for the built environment to find a symbiotic relationship with nature. We deny the very existence and operation of wildfires and other natural disasters, and our whole perception towards them is probably linked to our modern formation of rejecting the imperfection and objectifying occurrences that fall short of our ability to foresee. As technological progress makes the chance a complex yet conflicted cultural signifier, we are taught to look at the possibility of natural disasters as domains that are soon to be conquered. We barely look at them as phenomena that contribute to the shaping of our natural world and are therefore naturally unavoidable. Now, it is the time to shift the approach towards natural disasters and comprehend their “legal” right to emerge. It is the time to “work with fire”, to “understand the waters” and to “let the winds go”. So let that be a manifestation of natural law or even anthropological features of our time, wildfires will be around us.

Paradoxically, insignificant contributors of global warming pay a tremendous price when it comes to the ecological losses during wildfire seasons. Massive environmental and economic damage reminds us that while for some this is measurably a consequence of burning fossil fuels, cutting down forests and farming livestock, for others it can be a state of contradictions and logically unacceptable conclusions. As the contemporary political landscape has increasingly and more radically transformed this into a “we are-all-in-together”, it has helped the major contributors to shadow themselves among the details of these occurrences.

The destructive force of natural catastrophes can vanish decades of hard work and commitment, and as it appears obviously difficult for us to look at them as acceptable life features, the occurrence of wildfires triggers for a great number of cultural defenses. They can certainly be caused by natural occurrences, however most are caused by human activity. So, the very core of anxiety that accompanies the act of coexistence with them requires us to seriously revise our modern development in the first place. We have come to the point that we might even say that to be fully modern is to be anti modern. This was at first acknowledged by Marx and Dostoevsky who saw the battle against modernity as the only way to grasp and embrace the modern world’s potentialities. Today, it is already proven that by looking at this as an non-economic relationship we could put a halt to endless expansion, profiteering and exploitation of natural resources. As Françoise Choay, the French architectural historian, stresses it, “modern life exacerbated the anxiety surrounding the competence to build and the mirror of the past comes to reflect an increasingly heterogeneous and wide-ranging sweep of history”. So, our narcissistic approach of seeing the emergence of new buildings as monuments, and as means of moving forward to do away with natural barriers reinforces the presence of Anthropocene as the epoch of significant human impact on Earth. Our hastily grown confidence that we do possess the capability to rule the world by a scientific mindset, has built up a self-fulfilled identity that a continuous engagement in autonomous acts of creation is rather fundamental. This puts humanity in an unstable position with regard to nature, adding up on the anxiety that accompanies the very act of building. Therefore, the great challenge posed to developed cultures is now to construct a new form of competence: from building from nature towards building with nature.